Wisch: Origins Of Radio-Equipped Football Helmets Go Back To '62 Illinois High School Team

By Dave Wischnowsky –

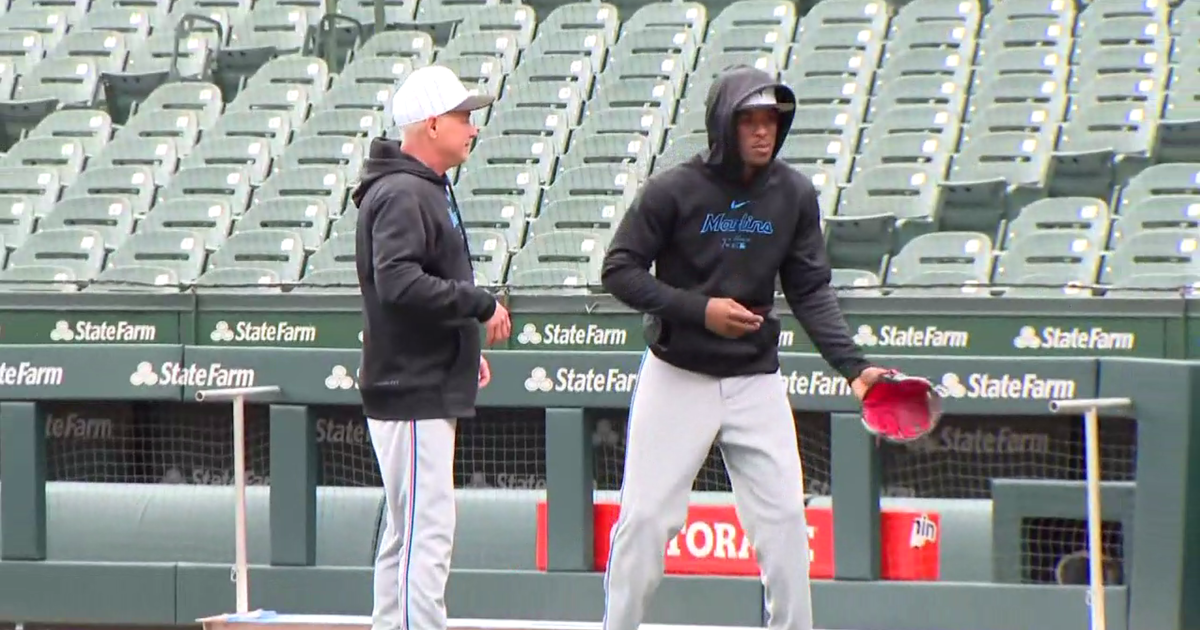

OTTAWA, Ill. (CBS) Colin Kaepernick hears voices in his head.

But it's not as if the quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers needs to see a shrink before Sunday's Super Bowl. After all, Baltimore Ravens QB Joe Flacco hears voices, too.

For that matter, so has every other NFL signal caller since 1994, when the league officially allowed teams to use wireless radio communication during games. Today, a quarterback couldn't shake the voices out of his helmet even with the help of a team psychiatrist.

At the start of this season, the NFL dumped the analog system that coaches have used to relay plays onto the field since '94 in favor of a digital network designed to improve signal clarity and connection. For a league that has often embraced new technologies at a glacial pace, the NFL's switch to digital was a significant advancement.

But it wasn't nearly as momentous as the advancement made more than five decades ago by a small-town Illinois high school that invented and employed its own radio-equipped football helmet during the early 1960s. So successful was this radio system for the Pirates of Ottawa Township High School that after four seasons they ended up getting the thing outlawed by the Illinois High School Association.

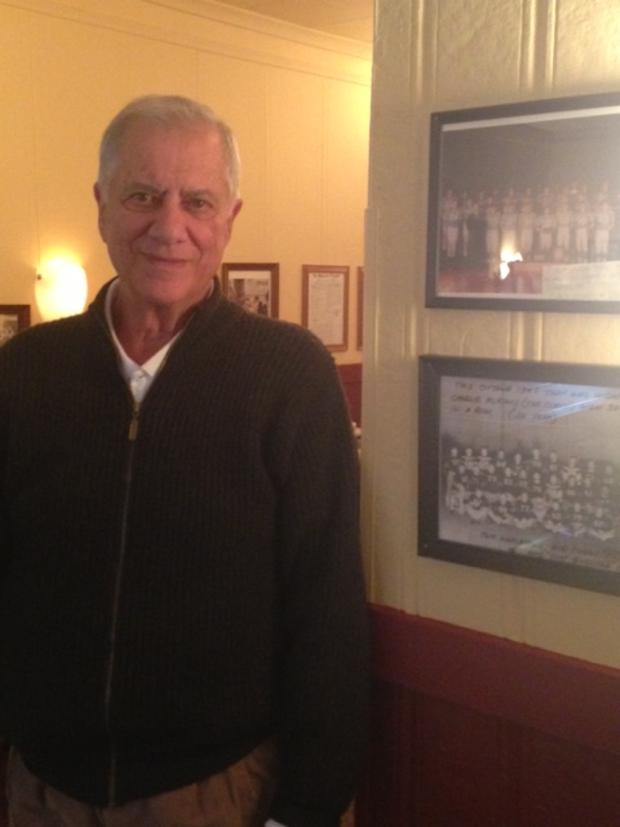

"And in (Illinois) high school today, you still can't use electronic communication," retired OTHS electronics teacher and football coach Bob Poggi, 82, recounted to me recently over lunch just outside of Ottawa, a town of about 18,000 nestled at the confluence of the Fox and Illinois rivers 85 miles southwest of Chicago.

In January 2003, I was working as a columnist for The Daily Times in Ottawa when Poggi and other former Pirate coaches and players shared with me the fantastic tale of the school's radio football helmet, which I wrote about for the newspaper. Almost 10 years later, on Dec. 29, Poggi and I got the chance to talk – and laugh – about the story once again while we feasted on the enormous breaded pork tenderloins that the Ottawa area is known for.

And, as the 49ers and Ravens prepare to bark plays through their helmets during Super Bowl XLVII, I wanted to revisit this old-time pigskin story that Ottawa is also known for – locally, at least. The following is a recounting of the town's colorful tale using the stories that coaches and players shared with me a decade ago when I was writing for The Daily Times. I'm now broadcasting them to you – much like the Ottawa Pirates broadcasted with each other on the gridiron 50 years ago.

Introducing Radiohead

"We were ahead of our time," the late Dean Riley, a former assistant football coach at OTHS, told me 10 years ago as he recalled Ottawa's "Golden Age of Radio."

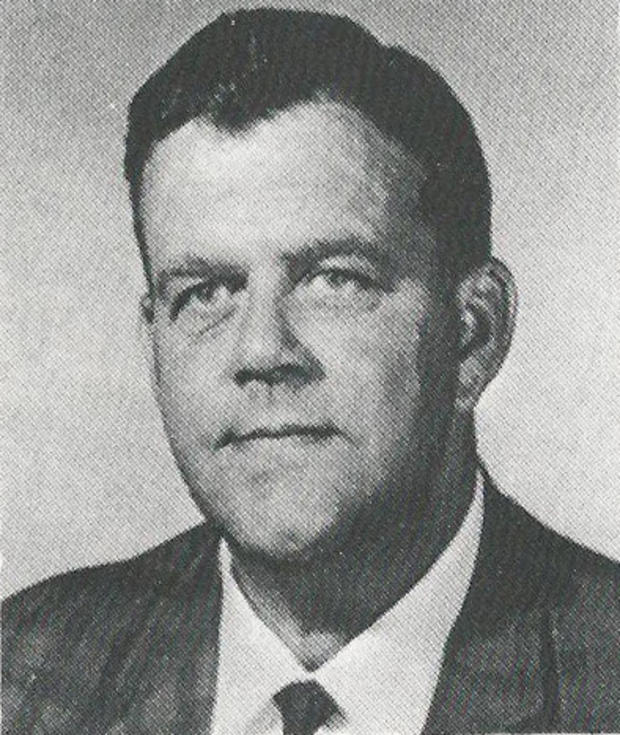

That era began shortly after the Pirates wrapped up their 1961 campaign with a perfect 9-0 record behind the guidance of legendary coach Bill Novak. Never one to rest on his laurels during his 25 seasons as a larger-than-life figure on the Ottawa sidelines, Novak quickly set his staff's sights on preparing for the next year.

"The quarterback situation wasn't clear for 1962," explained Riley, the team's offensive coordinator under Novak. "Our (upcoming) senior quarterback was hurt and we didn't have a quarterback in the junior class, for some reason. So, Danny Battles had been the freshman QB, and we were going to bring him up to the varsity even though he had never even played in a sophomore game."

Understandably, the OTHS coaching staff was concerned about having such an inexperienced QB leading what was expected to be another powerhouse Pirates team in '62. So, Poggi – the school's electronics teacher – proposed a solution.

Sort of.

"I said to Novak, kind of kiddingly, that I could probably put a radio in (Battles') helmet," Poggi recalled. "And that was all it took."

Cut from the same houndstooth cloth as Bear Bryant, Novak's toughness and fiery passion as a football coach remains the stuff of legend in Ottawa to this day. From 1947-71, the imposing figure of Novak reigned over the Pirates football program, piling up a 167-46-12 overall record (.784), including a remarkable 120-11-4 clip (.916) between 1957 and 1971.

In addition to his success on the field, Novak also was a visionary off it, having invented and patented a "donut-hole" facemask during the late 1950s, according to his former coaches. However, when helmet companies such as Riddell opted to shun outside facemask designs for liability reasons, Novak's financial venture ended up being a loss for a man who didn't suffer many of them.

It was that same foresight, however, that was sparked when Poggi, a 1949 OTHS grad who earned bachelor's and master's degrees in electronic engineering from the University of Illinois, floated the radio helmet idea. Novak demanded that he bring the vision to life, and Poggi went on to develop an innovative design in which he laid out radio wiring in a mesh form and glued it to the top of a football helmet before replacing the helmet's foam lining. In the top of the helmet, he then drilled a small hole for the radio's coil and topped things off by installing a transmit-receive speaker in the ear-flap.

"You could press the ear pad and talk just like you can on your cell phone," Poggi explained. "I thought (the radio helmet) was a good idea. It stopped people from running in and out to the get the plays from the sideline."

It also helped the Pirates stop their opponents. With valuable guidance pumped into his helmet from the sideline, Battles went on to lead Ottawa to another 9-0 mark in '62, and the Pirates racked up a record of 21-3-3 over the following three seasons.

Pumping Up The Volume

In fact, such a hit was Ottawa's radio helmet – a cruder form of which the NFL had banned in 1956, but the IHSA and NCAA had no existing rules against – that word about it even leaked to colleges such as Iowa, Purdue and Navy. Poggi said he spoke with coaches from each of those schools, all of them curious about how the system worked. But as it turned out, they weren't the only ones expressing interest in the helmet. Even Papa Bear Halas wanted to know more.

In 1965, according to Poggi, Chicago Bears assistant Abe Gibron made a trip out to Ottawa to talk with him about the intricacies of the radio helmet. This was in spite of the fact that the NFL had outlawed electronic communication nine years earlier and wouldn't re-institute the technology until nearly three decades later, in 1994.

With pro and college coaches getting wind of the helmet, it was only a matter of time until word about it leaked out to Ottawa's high school rivals, as well.

"Once, we were playing Mendota," Riley recalled 10 years ago. "My brother-in-law taught there and was in charge of security. During the game, a policeman came up to him and said he was picking up our play calls in his squad car.

"My brother-in-law said, 'No, they wouldn't be doing that.' But then he got in the police car and heard us. I had a hard time explaining that one."

Cops, it turned out, weren't the only ones tuning in the Pirates on the radio dial. Opposing fans figured out how to do it, too.

"People tried a lot of different things to screw up the reception," Jay Bernadoni, the Pirates' quarterback in 1965, said in 2003. "I remember we were playing (Spring Valley) Hall at Hall and some kids had gotten our frequency and were reading their geometry book to me. After that game, I had my geometry done for the year."

Math wasn't the only problem that Ottawa's QBs were often presented with. Sometimes, when the players expected play calls, it was traffic reports they received instead.

"The absolute worst was when (river) barges were going by," Poggi said about Ottawa's King Field, which rests along the banks of the Illinois River. "They'd want to know about the traffic on the locks."

Such an annoyance was radio interference off the river that, at times, Pirate QBs would start smacking the side of the helmet in an attempt to chase the voices out. But, Bernadoni explained, it wasn't just barges and opposing fans that were known to regularly burn his ears during games. Sometimes, his own coach was the culprit.

"(The helmet) was a tutorial for Coach Novak," Bernadoni said with a laugh, explaining how the hard-nosed coach would often grab the radio's phone from Riley and yell into his QB's ear – in mid-play.

"He would use it to expound on all his football knowledge," Bernadoni continued. "A few times (the radio) got broken because I also played linebacker. But a few times, it got broken because I pulled the wiring out."

Signing Off

Eventually, the Pirates' whole radio system broke down when it's believed that Ed Bender, the coach of Ottawa's archrival La Salle-Peru, blew the whistle on the Pirates before the 1966 season opener.

Just minutes before the game was set to begin at King Field, Poggi said that he and Novak were handed a restraining order from a Chicago police deputy that required the Pirates to turn off the radio helmet. So, they did, Poggi said – well, after a few minutes.

"Bob Burns was our quarterback, and they (the police deputy and Coach Bender) took the helmet off him down on the field," recalled Poggi, whose radio design had the wiring hidden underneath the helmet's foam padding. "The deputy looked at it, said, 'There's nothing in here' and gave Burns back his helmet.

"The funny thing was, we could hear everything they were saying from up on the school's third floor where we were looking down on them … Bill was pretty upset about the restraining order, but we quit using the helmet."

Turned out, it didn't matter much. The Pirates still beat L-P in the '66 opener and finished the season 9-0 en route to piling up an astounding 43-2 record – sans helmet – over Novak's final six seasons. And long after the fall of Ottawa's Radio Revolution, Poggi's contribution to Pirates football lore is still appreciated by the players and coaches from that era.

"A guy like Mr. Poggi was way ahead of his time with electronics," Bernadoni said a decade ago. "To devise something that was, not only compact enough, but durable enough to withstand the punishment it took, that was incredible.

"The coaches put it all together. And it's pretty remarkable for a little town like Ottawa to have had something like that."

Unfortunately, Poggi lost track of the radio helmet years ago – long before he first shared with me his memories about it back in 2003. And as we finished up our lunch in late December, its loss was something that he lamented. But while the helmet may be gone, its story is hardly forgotten.

And now, while watching the 49ers and Ravens coaches shout into their headsets during Sunday's Super Bowl, you can remember the helmet too.

If nothing else, Dave Wischnowsky is an Illinois boy. Raised in Bourbonnais, educated at the University of Illinois and bred on sports in the Land of Lincoln, he now resides on Chicago's North Side, just blocks from Wrigley Field. Formerly a reporter and blogger for the Chicago Tribune, Dave currently writes a syndicated column, The Wisch List, which you can check out via his blog at http://www.wischlist.com. Follow him on Twitter @wischlist and read more of his CBS Chicago blog entries here.