Medical Breakthrough In 3-D Printing And Fertility

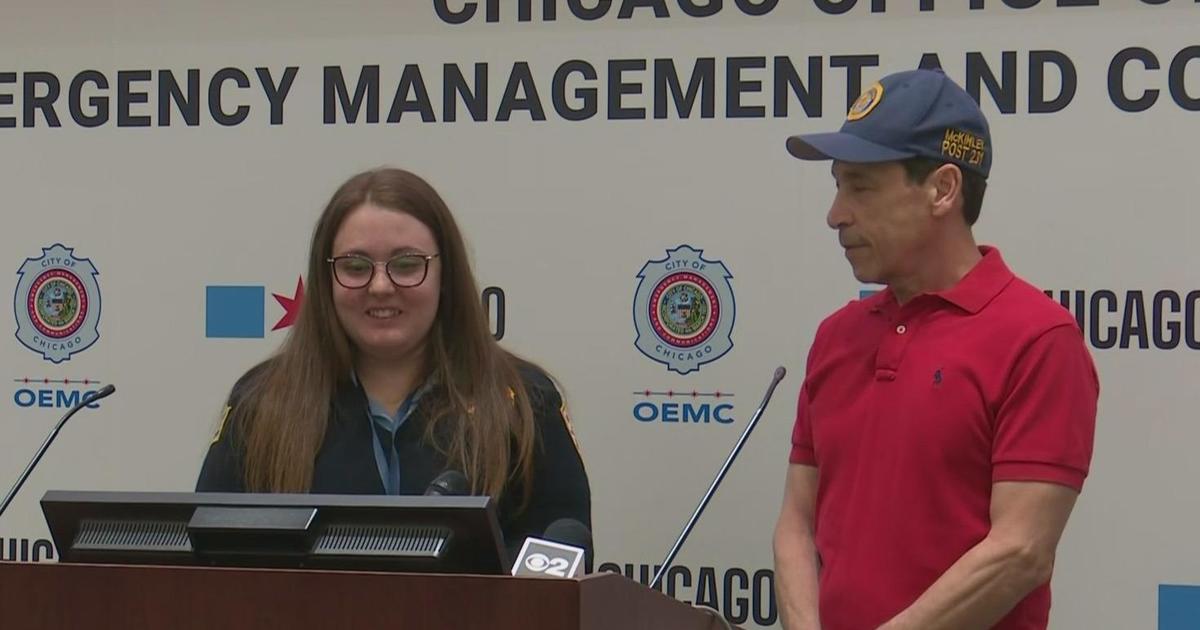

CHICAGO (CBS) -- 3-D printed body parts may seem straight out of a science fiction movie, but a recent medical breakthrough out of Northwestern University could use 3-D printing to benefit women who have lost their fertility.

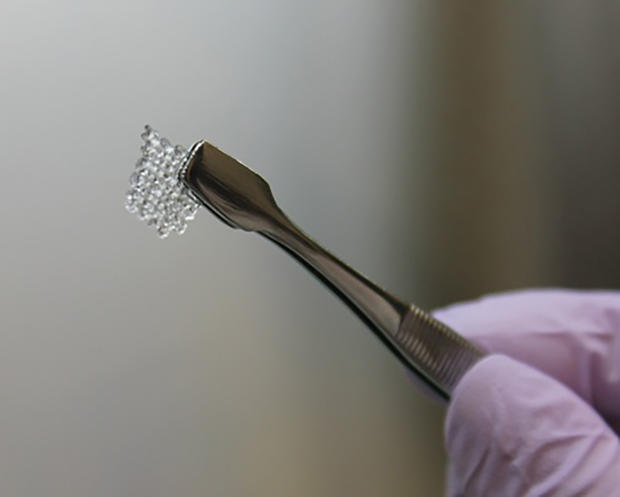

"We used 3-D printing, biological inks. We're basically using the building blocks of our internal organs, gelatin that comes from collagen and we're able to put that into the 3-D printer and basically instruct it to create the architecture of an ovary," said Teresa Woodruff, Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

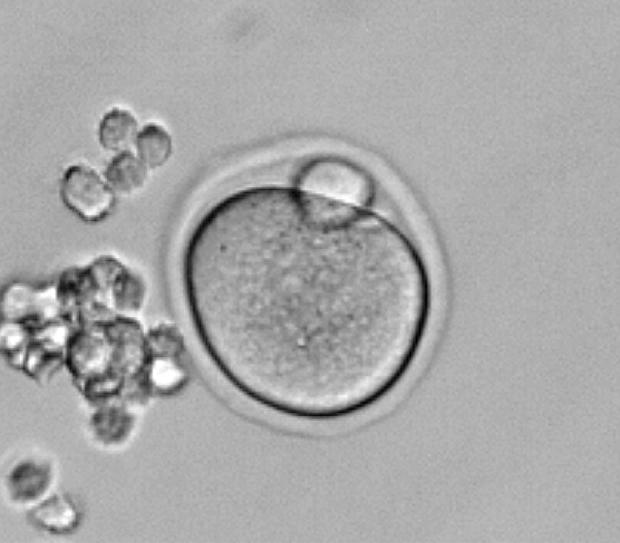

"We can then put in individual ovarian follicles, which is a single egg which is surrounded by the cells that make estrogen and those individual follicles are placed into the structure and we can transplant into mice," she said.

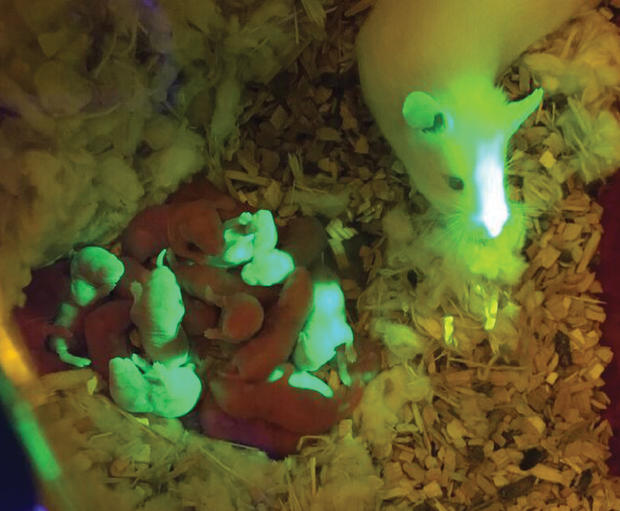

Woodruff said the prosthetic ovaries were implanted in mice who conceived and gave birth to healthy offspring. WBBM's Lisa Fielding reports.

"We had live birth from the female mice that we had sterilized by taking out the ovary so we completely restored their fertility," Woodruff said. "Live birth wasn't even our first goal. We were just trying to get the ovaries to function and get the animals to go through cycle. When we had live birth, it was spectacular."

She said this could one day be used to help restore fertility in cancer survivors and women with other fertility issues.

"Right now we are using this fundamental discovery to being to scale that bio prosthetic ovary for larger animals," Woodruff said. "We are going from mouse to the mini pig."

Such engineered ovaries could one day be used to help restore fertility in cancer survivors rendered sterile by radiation or chemotherapy.

In Northwestern's lab, the researchers call these 3-D printed structures "scaffolds," and liken them to the scaffolding that temporarily surrounds a building while it undergoes repairs.

"We are making clinical grade scaffolds and we're hoping to do some tests with those scaffolds to show that it can be safely used in women. We are hoping that we can eventually develop a successful bio prosthetic ovary that can help pre-pubertal children, girls who are being sterilized by cancer treatment enable them to go through puberty as well as young women who have fertility threatening conditions."

Woodruff said her team hopes to pioneer the procedure.

"We're the first to develop software for transplants that have been 3-D printed," she said. "The trachea has been printed and bone but no soft organs. As far as we are aware, this is a real breakthrough for not only reproductive biology but for those on the transplant lists and hopefully in the future there will be new bio incs for hearts, livers and other tissues."

While they aren't going to be printing out body parts anytime soon, she said human implantation is a real possiblity in the next five years.

"The revolution of being able to 3-D print internal organs is going to be move very quickly," Woodruff said.

All of the research is funded by the National Institute of Heath.

"The real promise of science and medicine is that tomorrow's patient will be treated better than today's. We hope tomorrow's cancer patient has many more options to not only survive their disease but survive with their fertility," she said.

The paper was published Tuesday, May 16, in Nature Communications.