50 Years Later, Illinois' 'Shoebox Scandal' Still Amazes

VIENNA, Ill. (AP) — A bedraggled John Rendleman II exited the St. Nicholas Hotel in downtown Springfield with the last bundle of a stunning find when he noticed his car had been towed.

Initially frantic, the university chancellor took a breath and then a cab to the city's tow lot. Rendleman's son, John Rendleman III, recalls his father's bemusement at the teenage attendant who gleefully demanded $20 — to retrieve a car stuffed with nearly $800,000 in cash.

Rendleman had gone to the St. Nicholas to clean out the suite of Paul Powell just days after the secretary of state's unexpected death 50 years ago, on Oct. 10, 1970, leaving behind the most notorious, unsolved political corruption mystery in Illinois history.

The "Shoebox Scandal," so-named because of some of the receptacles holding the money, including a Marshall Field & Co. Christmas box, shocked the state. There was $750,000 in the hotel and at least $50,000 in Powell's Capitol office. Subsequent investigations led to the eventual imprisonment of a former governor and some of the state's first campaign-finance disclosure laws.

When Powell died, Adlai Stevenson III, who was the Democratic state treasurer and three weeks from being elected to the U.S. Senate, told a reporter: "His shoeboxes will be hard to fill."

Only Powell could say how.

His government salary never topped $30,000 a year, yet Powell, a Democrat in solidly Republican Johnson County, accumulated today's equivalent of $5.4 million. A federal investigation pinned it on graft as secretary of state.

"It was impossible as an honest public servant to get along with Paul," Stevenson said this week. "He was not honest."

But Powell saw opportunities much earlier. In 1949 he won approval for parimutuel betting on harness racing on county fairs, with the blessing of new reform Gov. Adlai Stevenson II, the senator's father, according to Robert Hartley's book "A Lifelong Democrat." He supported horse-racing in Illinois over the next two decades and cashed in on stock in racetracks for which he determined the most favorable racing dates.

But the greatest source of revenue was likely the "Flower Fund," the money politicians regularly received ostensibly to buy flowers for funerals. Powell's gifts to churches and nursing homes were plentiful, said Gary Hacker, 81, who as a kid in the early 1950s did yard work for Powell. And needy children always had shoes and Christmas presents. But his receipts undoubtedly swamped his expenditures.

The government took notice when the cache was finally revealed on Dec. 31, 1970. From his $4.6 million estate, of which $1 million was in racetrack stock, the IRS got $1.7 million and the state, $223,000. News reports uncovered the interests that many politicians had in racetracks. Just a year later, former Gov. Otto Kerner, by then a federal appeals judge, was indicted and eventually imprisoned on a racing-related mail fraud charge.

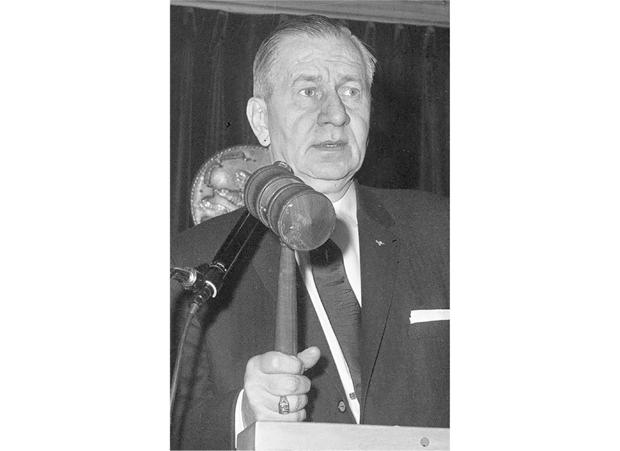

Powell, who was 68 when he died as an outpatient at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, was a legislative master who served as speaker of the House three times — including once when Republicans held a one-seat majority.

"He would go to any function anywhere, and people would just give money to him. Here's $100. His secretary would talk about going through his jacket at the end of the day and just pulling cash out of the pockets," John Rendleman III, a lawyer and Jackson County board member, said in his Carbondale office. In front of him were the lid to the Marshall Field shoebox and two attache cases that his father, a Powell friend and executor of the estate, discovered.

Powell was Herculean in delivering jobs and state projects. Tired of state money going to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, he funneled enough to make Southern Illinois University at Carbondale what it is today.

Taylor Pensoneau, Capitol correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch from 1965 to 1978, called him a "one-person public works department" for southern Illinois who went toe-to-toe with Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

"He was a very shrewd operator who helped deliver the votes needed for grandiose projects up north such as Chicago's huge McCormick Place Convention Center," Pensoneau said. "But not without a quid pro quo for downstate."

Such deals inspired one of Powell's favorite sayings: "I can smell the meat a-cookin." Another: "The only thing worse than a defeated politician is a broke one."

His ambition was evident early, according to Hacker, whose parents were Powell schoolmates. He laundered his high school football teammates' uniforms — for a price — and later ran his own restaurant.

He was elected to the House in 1934, served as speaker in 1949, 1959 and 1961, and was elected secretary of state in 1964.

After Powell came financial disclosure, lobbyist registration, and a ban on personal use of campaign funds. Economic interests require reporting but are one weakness that allow Illinois politics to remain potentially lucrative, said Kent Redfield, a campaign finance expert and professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

"If you want to get rich in politics (today), it's not through generating a lot of campaign contributions," Redfield said. "It's through the kinds of relationships that you have with lobbyists and economic arrangements with corporations that really are the avenue for the jobs that can come after."

(© Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.)