Chicago Police Raids Rarely Turn Up Drugs. So Why Do Judges Keep Signing Off On Bad Search Warrants?

CHICAGO (CBS) — Mary Ann Sparr was at home with her two children when Chicago Police officers burst through their front door.

"I didn't know if they were police officers or if they were somebody just ambushing my house to rob me," Sparr said.

It was Feb. 3, 2018. According to the search warrant, police were looking for cocaine and a suspected drug dealer based on a tip from a confidential informant.

While they searched Sparr's home and destroyed the family's belongings, she said it was the way officers treated her family that traumatized them the most. As her 16-year-old son slept, she said an officer jumped on his bed and put a gun to his head.

"[The officer] said, 'Don't you move. I'll shoot you in your f****** head,'" Sparr claimed. "The one officer looked at me and said, 'Shut your f****** face b**** before I handcuff you and slam your face to the floor.'"

What's worse, Sparr said, officers burst in just as her daughter, who has a disability, stepped out of the bathtub naked.

"It's terrible my daughter was violated that way in her home," Sparr said. "She doesn't even feel safe alone."

Officers didn't find cocaine or arrest anyone, police records show.

The Sparr family is among dozens who CBS 2 found were the victims of bad or wrong raids by Chicago police officers. In the Sparr case – and in every other search warrant signed in Cook County – there were multiple layers of accountability standing between police and their front doors.

But these layers often fail, a CBS 2 investigation found. And for the Sparr family, despite CPD's failure to independently verify the tip, a judge signed it anyway, calling into question just how often this happens.

Have police wrongfully raided your home? Tell us about it here.

'There is a Systemic Issue There'

Whether officers are seeking a search warrant to track down illegal guns, drugs or arrest a criminal suspect, they must prove they have probable cause to enter a home.

Police often receive crime tips from confidential informants, and some are paid. Officers must verify the information is correct by conducting their own independent investigation, which often includes surveillance and additional background checks.

Then, the search warrant must be approved by a police supervisor and an assistant state's attorney. Officers must also go before a judge to present their investigation in the form of a complaint for search warrant, a document that should detail the efforts officers took to confirm the informant's tip.

The judge's signature is the final step.

But judges are often quick to sign search warrants – especially those seeking illegal drugs – despite clear holes in the evidence presented to them by officers, CBS 2 found.

That's also despite CPD's low success rate for finding illegal drugs. According to the police department's own data, officers primarily target drugs in search warrants but failed to find any in 95 percent of search warrants seeking narcotics in a three-year period, CBS 2 previously reported. .

In the case of the Sparr family, Officer Baneond Chinchilla was the affiant, or lead officer, who presented the search warrant to then-Judge Mauricio Araujo.

Chinchilla claimed a confidential informant told him the informant had purchased cocaine from someone at the home multiple times, according to the complaint for search warrant. Chinchilla searched the suspect's name in CPD's Data Warehouse system, and the informant confirmed the photo was the same person who sold them the drugs. The informant then showed Chinchilla the home in which the drugs were allegedly sold, the complaint said.

But the complaint doesn't describe or indicate Chinchilla conducted an independent police investigation to verify the informant's tip was true, including any surveillance or drug buys. Judge Araujo approved the search warrant brought to him anyway.

But CBS 2 found numerous other judges who signed off on warrants in which police didn't independently verify the informant's claims. This includes CPD's wrong raid on the Mendez family in 2017. The warrant sought drugs and a suspected drug dealer, according to the search warrant.

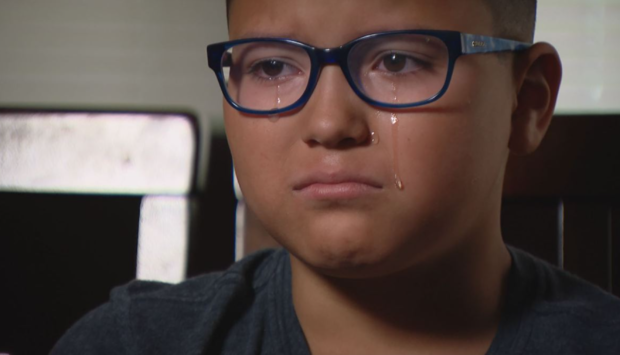

Ultimately, 9-year-old Peter Mendez, his younger brother Jack and their parents were on the other side of the door as police wrongly raided their home. Attorney Al Hofeld, Jr. sued the city on behalf of the family, alleging officers pointed their guns at them and traumatized the children.

"It was like my life just flashed before my eyes," Peter said.

The suspect police were looking for living in a different apartment unit.

In the Mendez case, a different Cook County judge approved the warrant, despite police failing to independently verify the information.

In a deposition, the affiant officer, Joe Capello, acknowledged the judge did not ask any questions about the warrant presented to him.

In 2015, two years prior to the raid on the Mendez home, police wrongly raided Jalonda Blassingame's home. Her son, Jaden, now 15, said officers pointed guns at him and his brothers, and ordered them to the ground.

"I felt scared for my life…I'll never forget it," Jaden said.

Police records revealed, once again, officers acted on the tip of a confidential informant, who told police weekly heroin sales were being made at the home by a man known as "Ace." Had officers done additional research to check the tip, they could have quickly found that information was incorrect.

It took just minutes for CBS 2 to search the suspect's name in a publicly available prison database. That search revealed "Ace" had been in prison at the time of the raid, serving a 40-year sentence for murder.

Despite CPD's lack of independent verification, another judge approved that warrant too. The Blassingames also filed a lawsuit against the city

"When we see data like what you are describing, it does give pause and it gives concern that there is a systemic issue there," said Sharon Fairley, a former federal prosecutor and former head of the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA).

Fairley, also a law professor at the University of Chicago, said judges have a critical role in protecting the sanctity of the Fourth Amendment by making sure – prior to approving the warrants – that police officers independently investigate and verify tips from paid informants.

"When someone's getting paid for something," Fairley said, "then they have an incentive to give law enforcement the information that they think that the law enforcement wants to hear."

Judge Shopping

In Cook County, approximately 70 judges can approve search warrants, according to the Cook County Chief Judge's Office.

Araujo signed off on more search warrants in Chicago than any other judge in a three-year period, according to police search warrant data analyzed by CBS 2. More than 1,166 search warrants listed his name as the judge.

"Police knew this was a judge they could go to anytime," said Ed Fox, an attorney who sued the city on behalf of the Sparr family.

Fairley said this idea can be referred to as judge shopping – when officers go to judges who they may have developed a relationship with and who they believe are more likely to approve their warrants.

"It does sound concerning that if you have a judge that's working that frequently with law enforcement, that they may develop a relationship to the point where it really undermines their ability to serve as a neutral and detached magistrate and making this probable cause determination," Fairley said, "because they get familiar with officers they get comfortable, and perhaps they're not scrutinizing the information that is brought to them, perhaps as diligently as they might."

In Chinchilla's case, Araujo signed off on more than half of his 98 warrants during a three-year period, CPD data shows.

Chinchilla also had a history of civilian complaints. There were 53 total complaints made against him, and 16 were for illegal searches dating back to 2006, according to the Invisible Institute's publicly available database. None of the complaints were sustained.

"This is the core concept of the Fourth Amendment and the Constitution," Fairley said. "That people should be free from unreasonable search and seizure, and the judge is supposed to play a role in that."

The CPD search warrant data obtained by CBS 2 appears to be the only information available that can show how frequently judges are signing search warrants and the outcomes. The Chief Judge's Office does not track when informant tips on approved warrants lead to bad information.

Judges also do not receive information about an informant who had previously given the wrong information, or about warrants being executed in the wrong home, before deciding whether to approve a search warrant, a spokesperson said.

While there's no system in place to track how often judges like Araujo sign off on bad warrants, he has been connected to a handful of publicized incidents that repeatedly called his credibility into question.

Araujo had signed warrants for two former officers, David Salgado and Xavier Elizondo, who used the warrants to raid and rob people. The officers were later convicted.

Araujo described to the FBI his relationship with Salgado as "more than an acquaintance, but not quite a friend," the Chicago Tribune reported, adding Araujo had attended multiple events with Salgado, including the wake for Salgado's mother, the officer's bachelor party in Colombia and his wedding in 2017.

The same month those officers were arrested, in May of 2018, the Chief Judge's Office changed a rule to prevent officers from going to any judge they wanted by requiring officers be assigned to a random judge. In response to questions for this story, a spokesperson said police officers do not currently choose judges.

Araujo also had troubling accusations levied against him by coworkers. During hearings before the Illinois Court Commission in September, two women – a court reporter and a police officer – accused Araujo of sexual harassment and unwanted sexual advances. Multiple people also said he made sexual comments about an assistant state's attorney.

In the first incident, which allegedly happened in 2011, Court Reporter Carolina Schultz said they were both in an elevator when Araujo asked her, "How much?" implying he was offering money for sex. Schultz said Araujo didn't correct her when she mentioned she had a boyfriend, and he was married.

[scribd id=484575229 key=key-YyFWCtw58KIYELUbzF85 mode=scroll]

CPD Officer Karen Rittorno described a similar incident she said happened on Aug. 5, 2016. When she went to Araujo's chambers to get a search warrant signed, Araujo tried to kiss her, she said. She performed a police maneuver called a "Back, Sir" to create distance between herself and Araujo, before asking, "Aren't you married?" to which Araujo replied, "Yeah," she said.

As they were leaving his chambers, Rittorno said Araujo grabbed her hand and told her, "Touch my butt."

Two years after that incident, Cook County Assistant State's Attorney Nina Ricci, who attended law school with Araujo, appeared in court on a murder case. Araujo said during the hearing that he was offended Ricci didn't acknowledge their past, and told another assistant state's attorney, Akash Vyas, "Something to the effect of, 'Maybe it was because I didn't have sex with her. Or maybe it was because I did have sex with her,'" Vyas said.

Araujo resigned shortly after the seven-member Commission found there was "clear and convincing evidence" that the allegations were true. The Commission had planned to issue a sanction, which could've included removal from the bench, the week after Araujo stepped down.

On Sept. 29, as he left the final hearing, CBS 2 attempted to ask Araujo questions about the questionable search warrants he approved. Araujo immediately began running down the street as soon as he was approached by a producer. He resigned the next day.

Living with Trauma

Mary Ann Sparr and her adult children have since settled their lawsuit with the city.

But Sparr said they continue to grapple with the aftermath of the bad raid on her home that happened more than three years ago.

"I feel so bad that my children had to go through that," Sparr said.

She questioned why the officers involved – and the judge who approved the warrant – didn't do their due diligence.

With judges being the final layer of approval, Fairley added they play a critical role in making sure civilians' Fourth Amendment rights are protected when officers seek search warrants.

This includes ensuring police conducted an independent investigation – not solely rely on the word of confidential informants.

"As the sort of gatekeeper, the judge should be looking for that additional corroborating evidence," she said.

CBS 2 contacted Chief Judge Timothy Evans' spokesperson with our findings. Through his spokesperson, Evans declined to be interviewed for this report.

In addition, CPD did not make Chinchilla available for an interview.

[wufoo username="cbslocalcorp" formhash="x1ewdf860s5k3vz" autoresize="true" height="828" header="show" ssl="true"]