New Illinois Law Is Supposed To Prevent Animal Abusers From Having Pets, But CBS 2 Finds There Is No Plan Or Guidance To Enforce It At All

CHICAGO (CBS) -- The State of Illinois says it's protecting animals – but how is it doing so?

A brand-new law is on the books preventing convicted animal abusers from owning pets or having pets in their homes, but CBS 2 found there's nothing in place to actually enforce it, and no guidance for law enforcement.

Nothing.

CBS 2's Tara Molina has been digging into this issue for weeks. She brought it to everyone involved, from the Illinois state representatives who sponsored it to the chief judges and probation offices directing it. Responses were mixed.

Meanwhile, some of the offices we reached with questions about enforcement actually first learned about the new law through us.

The new Illinois law aims to protect animals with no way to defend themselves – keeping them out of the hands of known animal abusers. Best friends – pets of all shapes, sizes, and breeds – are protected.

The new law says a person with two or more animal abuse or neglect charges cannot own or live in a household with any animal.

The law was approved as an amendment to the Humane Care for Animals Act and was signed by Gov. JB Pritzker on July 23, 2021. The law took effect at the beginning of this year.

The specific language in the state House bill that went on to become law is that it "(p)rovides that in addition to any other penalty, the court may order that a person and persons dwelling in the same household may not own, harbor, or have custody or control of any other animal if the person has been convicted of 2 or more of the following offenses: (1) a violation of aggravated cruelty; (2) a violation of animals for entertainment; or (3) a violation of dog fighting."

But we looked closer at the statute – and found that while the law means to protect animals from those who could hurt them, there's nothing in place to enforce it.

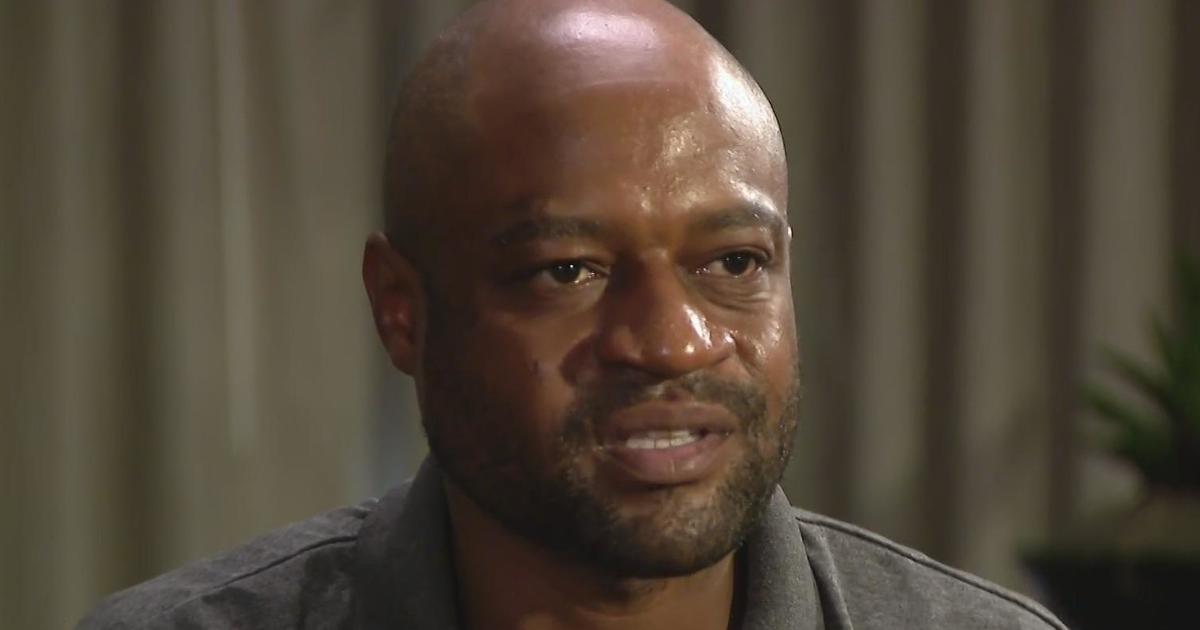

"It's just tricky," said Mamadou Diakhate, Executive Director of Chicago Animal Care and Control.

Diakhate was one of the first to whom Molina reached out when it went into effect Jan. 1.

"This law is important, but it has to be understood," Diakhate said.

And right now, it's not. Diakhate said city animal shelters haven't received any guidance on the issues such as how they should implement policies to prevent those who aren't allowed to own animals, or live in a house with them, from walking through the doors and adopting one.

We heard the same thing from other animal care and advocacy groups.

So Molina turned to those who made this new law happen, beginning with the sponsor, Illinois state Rep. Daniel Didech (D-Buffalo Grove).

Didech ignored Molina's interview request, and referred Molina to the Illinois state director of the Humane Society as the "best resource" to speak about the law – despite the fact that Didech himself was the one who sponsored it.

When Molina asked repeatedly how those who wrote the law envisioned enforcement, Didech replied simply: "It would be enforced the same way as anybody else who breaks a law or violates a court order. Law enforcement would investigate complaints and gather evidence. Prosecutors would make the case in a court. And the court will determine whether the accused person broke the law or violated a court order. If a violation occurred, the court would be able to punish the person just like any other instance when someone is found to be in contempt of court."

Molina followed up to ask Didech whether those who wrote and supported the animal protection law had any vision for enforcement that she had missed. She noted several departments had told us to find out if there is a plan, and about the possibility of a statewide animal abuser registry like the one already in effect in Cook County.

Didech replied: "I don't think you are missing anything. The vision is that it will be enforced like literally any other law."

Enter Marc Ayers, Illinois director of the Humane Society of the United States.

"I think enforcement will be relatively easy," Ayers said.

Ayers was the one whom Didech advised Molina ask about the law and its enforcement.

"We have been trying for a couple years to get the bill across the finish line," Ayers said.

A total of 31 other states have similar laws already in place, according to Ayers – who was surprised when Molina told him she had yet to find someone who understood how the new law should be enforced.

"The enforcement of this law will kind of be up to the judges themselves, who issue the order itself – the forfeiture," Ayers said. "It'll be issued by the judge and then left up to law enforcement to ensure animals are not in a dwelling."

That is not the case, according to the Cook County Chief Judge's office – which could be issuing such orders now.

Chief Judge's office spokeswoman Mary Wisniewski issued the following statement: ""Unless a defendant is sentenced to probation, the Act seems to provide no role for the court in post-conviction supervision. We don't have any information on tracking and enforcement. You may want to reach out to the people who sponsored this law, to see how they intended this to be enforced."

Wisniewski went on to say, unintentionally ironically, "You may want to reach out to the people who sponsored this law, to see how they intended this to be enforced."

Since Molina had already gone that route, she reached CBS 2 Legal Analyst Irv Miller, who put the issues with the law in the simplest terms.

"It's an absolutely vague statute – incapable of being enforced by any law enforcement agency," Miller said, "so it looks good on paper, but it's meaningless."

Law enforcement offices, tasked with enforcement, weren't willing to going on the record with their response to the new law. Miller explained a possible reason why.

"I interpret it as a poorly-written statute that gives law enforcement absolutely no guidance on how to enforce the statute," he said. "We don't know what the punishments are. We don't know if it's punishable by a ticket, by a fine. Is it a misdemeanor? Is it a felony?"

So Molina brought all of that back to Rep. Didech. She told the lawmaker, "With no guidance, no clear penalties and no enforcement mechanism, enforcement of the statute is being called difficult or impossible."

Didech replied:

"It's the same way that any law breaking is investigated. A police officer needs probable cause to conduct a search. The officer needs to observe the law breaking himself, or witnesses need to cooperate, or there has to be video or photographic evidence, etc.

"You have pinpointed why it's often challenging to solve any crimes, not just animal-related crimes. It's a process of gathering evidence without violating the constitutional rights of the person being investigated."

But Miller said there's really a different point here.

"There's a lot of laws on the books," Miller said. "They usually say how you enforce the law, and they usually tell you what the penalty is."

Molina also brought all of this back to the Humane Society's Ayers – asking him if any new education initiatives or moves for more specific guidance on how to enforce this law are in the works. This was his response:

"I haven't heard from anyone else on this subject, either. If those entities are interested in providing us language to help make the law 'enforceable; then we'd be happy to assist and offer that language up next legislative session.

"I think my focus and the sponsors were to simply give the statutory authority to the judges to make the confiscation mandatory. That's all. I'm still puzzled at how just providing that authority to a judge that it can't be enforced and after 2 years of being an active bill, not a single entity made that known during the process. Regardless though, I'd be happy to continue working on this till we have a product that's fully enforceable."